Conversations with care homes a series by My Home Life England

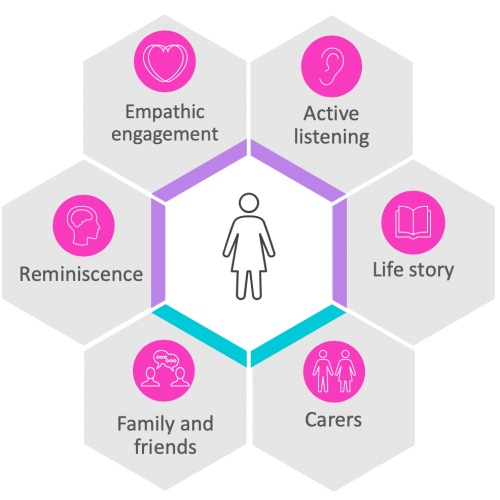

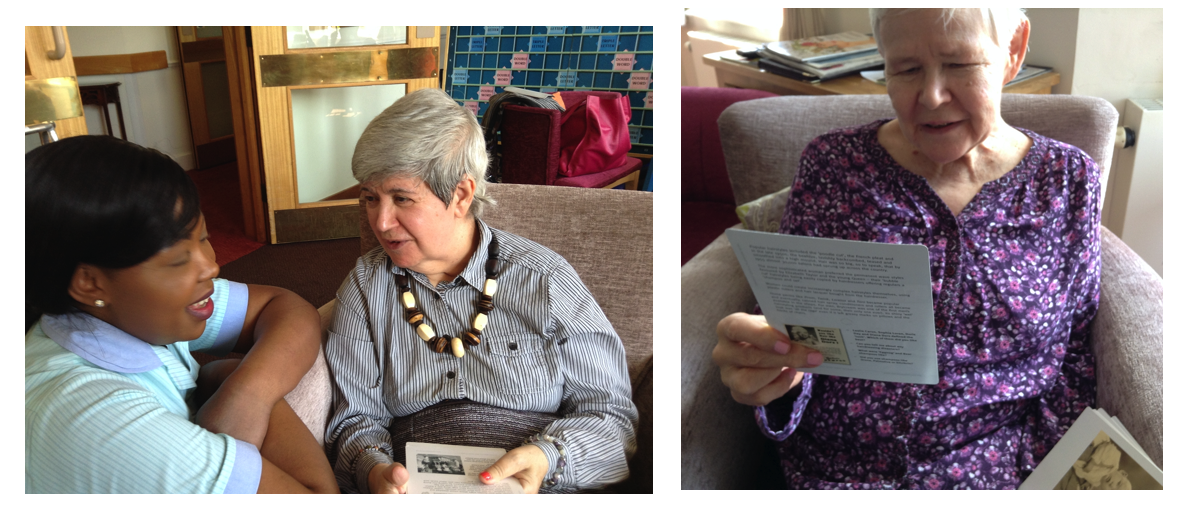

‘Conversations with Care Homes’ is a series by My Home Life England (MHLE). In Episode 7 we focus on how best to support care home residents living with dementia during COVID-19. The pandemic has posed additional challenges for those living with dementia – for example the disruption of familiar routine, the need to socially distance and wash hands more regularly, and the impact of staff wearing more PPE. We share stories, tips, methods and signposting for how best to support residents living with dementia at this difficult time.

You can see more Videos from My Home Life here >>

A message from My Home life to the care home community:

You are doing an incredible job in challenging circumstances. You continue to make such a positive difference to people’s lives – thank you. We see you, we appreciate everything that you are doing, and we want you to know that My Home Life England is always here for you. Keep up your fantastic work and please do get in touch if you are able, we’d love to hear from you.

Please get in touch! If you have any stories to share, please contact us at mhl@city.ac.uk or call 02070405776 For more information about My Home Life England, please visit our website or find us on Twitter & Facebook – @myhomelifeuk

About My Home Life

My Home Life was founded in 2006, by National Care Forum in partnership with Help the Aged (now Age UK) and City, University of London.

It is a social movement for quality improvement in care homes that has spread nationally and internationally.

The success of My Home Life lies in our four evidence-informed guiding principles: Developing best practice together, Focusing on relationships, Being appreciative, and Having caring conversations.

“A diagnosis of dementia for a person is also a diagnosis for the whole family.”– Four letters that make communicating with a person with dementia more real.>>